From Prosecco to Nastoïki: The Adventures of two Italians in Russia

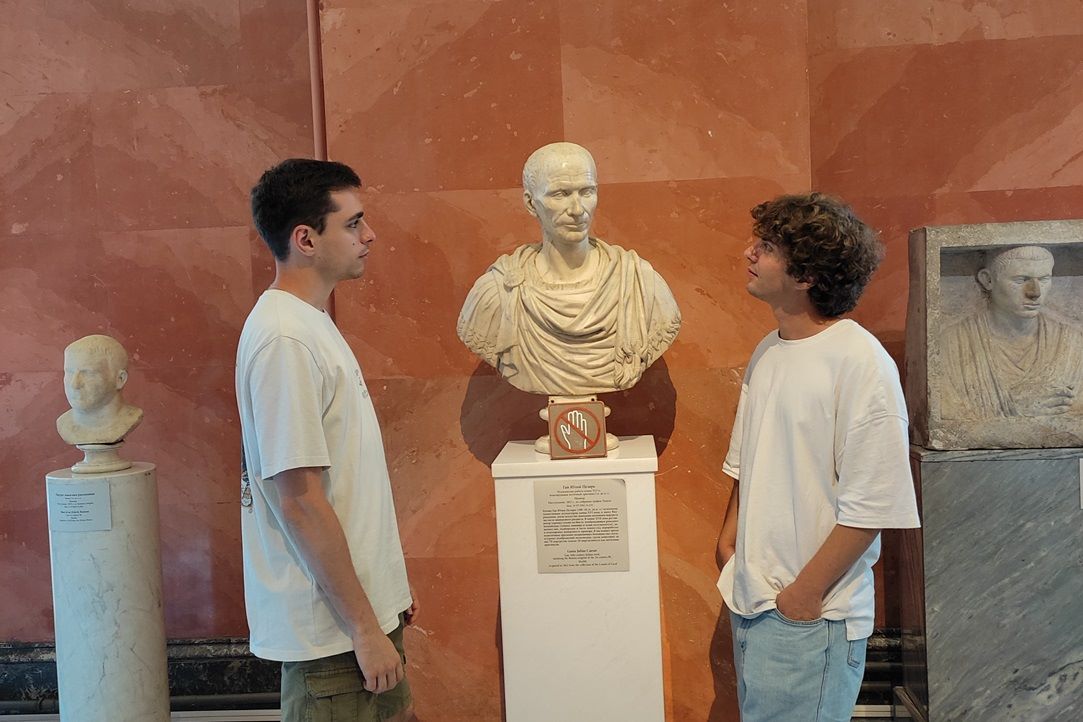

Sitting at a table in one of their favorite bars - Sosna i Lipa, near the Chistye Prudy in the center of Moscow - Alessandro Vendramin, 24, and Fabrizio Talamini, 25, enjoy a draft beer on one of their last evenings together in Moscow. The two Italians are from Veneto region, in Northern Italy. Fabrizio is from Conegliano, a little town famous for his Prosecco, while Alessandro is from Jesolo, home to one of the most important sea resort of the Adriatic coast. Yet it is in the student city of Verona, during one class of the renowned Slavist Stefano Aloe, that they met, in 2019. After they finished their Bachelor's degree in Languages and culture for international trade, despite living close to the economic heart of the third economy of Europe (in terms of GDP), the two Italians decided to leave Italy for Russia. Hence, in February 2022, they landed almost simultaneously in Moscow, first for a six-month preparatory course, then deciding to enroll for a Master's degree in International Business.

Now, after having been inseparable for two years, the two friends will see their paths drift apart: Fabrizio will head back to Italy for an internship with the Delonghi company in Treviso, half an hour from his hometown, while Alessandro will move in with his girlfriend, whom he met on the university benches, in a large apartment overlooking Moscow City. This final evening is for them an opportunity to take stock of their atypical shared journey.

Fabrizio: In any case, I won't be coming back any time soon: my visa is about to expire and the journey is too expensive. I'll miss my graduation in June and will probably have to make do with a digital version. If the question is whether Russia will occupy a place in my professional career, I don't know yet. I'll seize the best opportunity, but if I have to choose between, say, India and Russia, I'll choose Russia.

Alessandro: For me, it will also depend on professional opportunities, but as things stand, it seems that I'm more likely to find the right job elsewhere, in the right company - not in terms of salary, but in terms of interest and development possibilities. If my prediction proves correct, Russia will remain just a place I love, and nothing more. Maybe I'll move to Europe, or China.

I've studied Chinese and I'd love to be able to put it to good use, and avoid losing my level. I'm also attracted by certain cultural aspects. It's very different from both Western Europe and Russia. I'm struck by their humility; I've never met a Chinese person who imposed himself or had an overpowering personality. I think it's a country I'd love to discover, either as a tourist or by working there, if I were offered something. Anway it would be a better option than Italy.

Fabrizio: Because we're Italians. We've lived here all our lives, and we can go back whenever we like. In the meantime, we prefer to discover the world. And then, quite frankly, I don't think Italy has a bright future ahead of it. And I'm not just saying this because of the new Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni: the responsibility is collective, and the country is heading for difficult times. Besides, Italy is not alone in facing difficulties. Sometimes it seems to me that the whole world is about to collapse, so let's explore it before it does.

Alessandro: More pragmatically, this decision was partly motivated by the lack of professional prospects. Even the biggest Italian cities don't have the same feverishness as Moscow. I'm frightened by the stories I hear from my friends in Milan. It's certainly not a city where I'd like to work.

Alessandro: One can trace my interest in Russia back to my mother, who is of Czech origin. I spoke good Czech as a child, with her and her family. So, when I entered high school, I chose Russian as an elective, thinking that the two languages would be similar. They turned out to be more different than I expected, and it was a difficult start. After a few years, I got the hang of it, and even enjoyed the difficulty itself, I'd say.

Fabrizio: I also chose Russian as an option in high school. The language served as a gateway to culture. As you may know, when you start to take an interest in Russian literature, you quickly become fascinated by the country. To this interest was added the desire not to waste the years spent learning the language.

Fabrizio: Professionally, I don't yet know if it makes sense, but I do know that if I hadn't come to Russia after my Bachelor's degree, I would have regretted it all my life. February 2022 wasn't the best time to move to Russia. I took a risk. Many career prospects had been shattered, and it would take years to rebuild the links between here and there. So it was more a decision that came from the heart.

Alessandro: Maybe, but I'm not sure that strategically it's such a bad decision. Sooner or later the situation will change, and we'll need people who are familiar with the language, the culture, the local business environment, and so on.

Fabrizio: The first few months were extremely strange. The rouble was on a tear: when it depreciated, we enjoyed an extremely comfortable budget, and then it rose again at full speed. This emotional yo-yo affected every aspect of life in Moscow. And it was difficult to socialize because Russians had other things on their minds and didn't seek the company of strangers.

Alessandro: Yes, contact with Russians was difficult at first. In particular, I had the feeling that they systematically felt obliged to explain to us their perception of what was happening.

Fabrizio: And then there were all the aspects that weren't linked to this specific context. For us, coming from small Italian towns, we had to acclimatize to a megalopolis of 15 million inhabitants. Everything was new, not just the language.

Fabrizio: The main problem was our flatmates stealing our cutlery. Oh, and our room flooded every week because of a plumbing problem. But they fixed it after a month. Overall, it wasn't a traumatic experience, there were some very nice people.

Alessandro: Yes, incredible people with whom we would never have met in Italy: Iranians, Kirghiz, Afghans, Indians, Chinese, Palestinians, ... nationalities that are not so common in Europe. Maybe all big cities are cosmopolitan, but Moscow is cosmopolitan in a way that we wouldn't have been able to experience in a European city.

Fabrizio: And even within Russia, meeting students from Yakutsk or the Republic of Tyva made a deep impression on me. There's a gulf between the environments where we respectively grew up, and such encounters could only have happened in Moscow.

Alessandro: There were some very good things. Many of the professors were not theorists but came directly from the professional world and had concrete experience to share. I liked the way they built bridges between theory and practice.

Fabrizio: I was expecting it to be harder, but there were some excellent courses, such as Corporate Finances. I was a little disappointed by their offer in terms of international experience for academic exchanges, because the only partner universities were in Europe, whereas I would have liked to have had the opportunity to go to India or South America.

I think what struck me most was the vitality of the alternative culture, i.e. the bar and club culture. Polye, Mutabor (both have since closed their doors, ed.), or even Sosna i Lipa, where we're sitting now... These places are both extremely underground and cool, friendly. And that's what I miss the most, because we don't have anything like that in Italy. There's a lot of talk about the quality of classical culture in Russia - ballet, opera, theater. I don't doubt it, but the truth is that I haven't experienced it and I haven't sought it out. Maybe because in Italy, this classical culture is everywhere.

Fabrizio: I knew Alessandro by sight in Italy through my studies and because he was a friend of my roommate, but we weren't very close. Before coming to Russia, we'd maybe shared a drink together once or twice at most. He seemed like a nice guy, he had very good grades, that was all. But when we got here, we clicked right away, and it just got better and better.

Alessandro: Absolutely. I can say that now as we’re about to part, Fabrizio became one of my best friends.

Fabrizio: I think we supported each other and pushed each other forward.

Alessandro: I was reluctant to enroll at the Harbin Institute of Technology for the Master's degree, but in the end, if I stayed in Moscow, it's partly thanks to Fabrizio.

Fabrizio: The metro, the chance to go to a different bar every weekend, speaking Russian, the amount of new people...

Alessandro: Yes, all that, plus the Gorki Park, and the view from my apartment of the Radisson Collection Hotel, one of Stalin's Seven Sisters.

Interview by